Our "environment" includes both social determinants of health and physical environmental determinants of health. Social impacts on health are embedded in the broader environment in which we live.

Our psychosocial environment includes our responses to stressors in our lives, from temporary ones such as a traffic jam to major stressors such as war, homelessness or major disease. Our relationships with family members, friends, colleagues and other individuals and groups with whom we interact in our communities are an important part of this environment. These can impact our capacity to deal with stressors. Nurturing, supportive relationships allow us to better access all our innate resources to respond to stress in positive ways.2

Conversely, relationships that do not foster growth, learning, resilience and resolution of problems can themselves be a source of stress and can contribute to poor mental and physical health outcomes.

Stress and the Body's Response

Our bodies, families, communities and lives are embedded in a complex network of systems. The degree of support in the environment can shape a person’s resilience. Likewise, an environment that is stressful can foster disease. The conditions of a person’s social and psychological environment—those in which they are born, grow, live, work and age—are known as the social determinants of health. These conditions are shaped by the distribution of money, power and resources at global, national and local levels.3

Risks for Stress: RiskscapesA riskscape, or landscape of risks, captures the overlapping threats to health occurring in a physical location that increase risk for disease.4 An example of overlapping risks can be seen in impoverished neighborhoods,5 which often experience many of the stressors listed above simultaneously. We discuss poverty in more detail on our Socioeconomic Environment page. Minority status, age and gender further interact to increase risk for disease.6 Individuals experience additional adversity when they live amid wealth and affluence but do not share those resources.7 |

To better understand how the psychosocial environment impacts health outcomes, one must understand how these conditions interact with the human stress response. The stress response within the psychosocial environment can trigger disease.

Stressful Environments and the Social Ecological Model of Health

The rise of chronic disease is a complex and growing problem for public health in the US.8 Stress, particularly exposure to long-term chronic stress, is associated with the majority of chronic health conditions.9

Social Ecological Model of Health

The Social Ecological Model of Health Promotion (SEM) describes how our psychosocial experiences are nested inside layers that influence health and well-being:10

- individual

- interpersonal (familial)

- communal (neighborhood)

- societal

The SEM is particularly useful in allowing researchers to study stressors from the micro scale (cellular) to the macro scale (social policy), positioning their work in the larger social ecological context.14 Layers are labeled with their corresponding social determinants of health.

graphic by Lorelei Walker; click to zoom

Policies that affect economic and social determinants (top level) can decrease access to income and education, and have powerful effects on neighborhood stressors.15

These policies shape disparities in local environments (second level)16 such as poverty, pollution, crime rates and political power.

Daily opportunities (third level) create or suppress nurturing environments and govern the frequency and intensity of daily hassles (discrimination and microaggressions).17

These layers affect our daily behaviors and patterns (fourth level) and daily interactions.

As these pressures funnel down from the political to the community to the individual, they become observational cues (fifth level) that the environment is threatening, unpredictable or uncontrollable and thus stressful.18

Upon activation, the brain sends signals to the body to mount a stress response.19

Allostasis: The Body’s Stress Response

When the brain interprets a threat, it sends a cascading signal through the body that causes a stress response, known casually as "fight or flight" and more formally as an allostatic response.20 See The Human Stress Response System at right for more detail.

In healthy doses and supportive environments, this response is tempered and can foster learning.21 In adversarial environments the allostatic response can manifest as chest pain, heart palpitations, headaches, dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), intestinal cramping, anxiety, panic, immobility, frustration, muscle tension and inflammation.22

These reactions can be exhausting and imprint a strong memory of fear on the brain.23 Fortunately, a feedback system in the brain is capable of stopping the stress response. 24 Terminating the stress response and restoring the body to pre-stress response states is important to protecting the body’s long-term health.25

How our bodies respond to stress varies across the population,29 determined by genetic predisposition30 and previous experiences including exposure to maternal stress signals before birth31 The typical responsivity can be modified by genetic predisposition32 but is generally neither amplified nor repressed.33 This neutral programming is optimal in moderately stressful environment where life is not overly threatening nor consistently safe. Over an individual’s life, neutral programming is optimal in balancing the risk for internal burnout from repetitive stress burden and survival in adverse environments long enough to maximize periods for mating and parenting.34

Chronic Stress and Disease: Weathering

With repeated exposure to stressors, the HPA axis activation is sustained, and stress signals continue to flood the body. This sustained activation delays the onset of restorative repair and pushes the body into pre-disease states.35 Chronic stress acts on the cardiovascular, metabolic, neuroendocrine and immune systems:36

- Persistent epinephrine surges can damage blood vessels and arteries, increasing blood pressure and raising the risk of heart attacks or strokes.

- Elevated cortisol levels create physiological changes that help to replenish the body's stores of energy that are depleted during the stress response. Cortisol increases appetite and also increases storage of unused nutrients as fat, which can contribute to the accumulation of fat tissue and weight gain.

Over time, stress deteriorates health and resilience. This process is referred to as weathering.37 Just as a flag that weathers many storms begins to fray, so too does the body when it experiences harsh environments of social inequity.38 The health outcomes are mental illness, chronic disease morbidity and premature death.39 In short, stress causes physical changes that impact our health and functioning.

The frequency, duration, intensity, source, target and proximity of stressors influence the extent of the stress response. The duration of response can increase an individual’s risk for physical and mental burnout. Stressors that are higher intensity or longer duration carry a high internal burden (allostatic load).40 Over time this internal pressure forces body systems to adapt in ways that foster pre-disease states.41

In weathering, each body system adapts to this internal pressure through secondary changes:42

| Dysregulation in these areas | can cause these secondary changes.43 | With chronic stress, such changes increase the risk for these conditions:44 |

|

|

|

Through this process, chronic stress responses cause weathering on the body, eroding health status.49 As years turn into decades, the physiologic changes (such as hypertension, metabolic disorder or anxiety) may become irreversible, often increasing co-morbidities, potentially increasing maladaptive coping mechanisms (such as social aversion, drug and alcohol dependence) and decreasing life expectancy.50

Through these mechanisms social structures can get under the skin, alter our bodies and cause disease. The loss of productivity and financial burden of systemic disease further erodes family and community resilience, especially when the chronic stress starts in childhood.51

Disadvantaged Populations

Lower social classes experience longer durations of chronic stress, such as lengthy unemployment or institutionalized discrimination. Those with less power experience barriers to achievement of life goals, such as high costs of educational programs or lack of childcare options, inadequate recognition and rewards for personal qualification (such as gender pay differences) or for invested effort in the workplace. In the US and other White-majority countries, minorities and women in these environments are exposed to more chronic stressors than their White male counterparts due to differential expectations resulting in role strain and interpersonal conflict.52

Both the sources and frequency of stressors are not distributed equally in society, with heavier burdens borne by those with less advantage.53 These systems of inequity create differences in health outcomes, known as health disparities.54

Stressful Environments and the Developing Child

Our stress system responds to environmental conditions even before birth56 and is especially sensitive early in development.57 Glucocorticoid receptors are found in most fetal tissue and in the placenta, suggesting they are capable of responding to high maternal cortisol. Early-life experiences shape our stress response and therefore the impact stress has on our health over the life course.

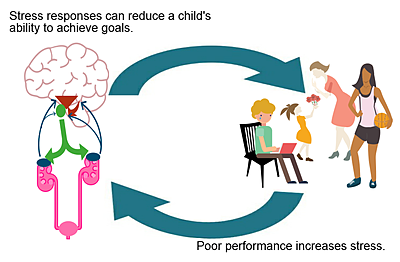

A person’s individual responsiveness to stress signals can shape brain development.58 Highly responsive individuals demonstrate better learning and health outcomes in supportive environments and worse health outcomes in high adversity environments.59 Supportive environments foster better mental and social learning, increase memory and improve decision-making; in such environments, children have adequate time for stress response termination and are generally characterized by openness to information.

In negative environments, however, high responsivity magnifies the body’s response to intense or chronic stressors, increasing the risk for weathering over the life span. Highly responsive individuals can become hypersensitive to social feedback and psychological manipulation, both capable of detracting individuals from achieving goals.60 This increases the risk for future stressful experiences, further increasing the risk for weathering.

Stress responsivity shapes the intensity of weathering and has implications for later adult health outcomes.61 Responsivity biased toward either under- or over-reactivity can predispose children to adult disease.62 For example, overexposure to maternal stress hormones before birth can restrict birth weight and predispose the developing child to hypertension later in life.63 Effects of parental stress, such as reduced opportunities for bonding and distant parent-child relationships, significantly increase the risk up to fourfold for a child to experience anxiety, depression, diabetes and heart disease as an adult.64 Higher prenatal glucocorticoid exposure is directly associated with higher circulating glucocorticoids in adulthood, and both are associated with increased hypertension and hyperglycemia and changes in adult behaviors.65

Brain Changes

With exposure to chronic stress, the brain changes shape, reducing connections that support nuanced cognitive function, self-regulation and memory; this process is less reversible as a child ages. Through these changes, chronic stress increases the likelihood of aggression, vigilance and anxiety.69 Because an individual suffering from these changes and conditions is handicapped in becoming a nurturing parent (although many people do overcome adversity and become terrific parents), the effects of stress can be self-perpetuating down generations. Through stress biasing, the social determinants can become multigenerational stimulants of chronic disease.70

To the individual, there is a cost for high responsivity. Early life stressors that reshape the brain affect hippocampal and amygdala development that can affect a child’s transition into adolescence. Chronic early stress impacting social learning may predispose teens to depression and substance abuse, both feeding into adult chronic diseases.71 This is a vicious cycle of early childhood adversity. The stress that parents experience can have direct influences on a child’s biological capacity in responding to future stressful situations.72 The parent-child relationship, in utero and through development, provides experiential information that programs stress responsivity.

Telomere Changes

Telomeres are structures on the ends of chromosomes that protect and stabilize chromosomes. They are essential for avoiding cellular dysfunction. Telomere length is reduced with age, smoking and stress, and shorter telomeres can impair health.73

Telomere length in specific blood cells is viewed as a biomarker for cellular aging that is closely associated with age-related and chronic diseases.74 This biomarker may reflect population-level weathering in communities. For example, a study of nine-year-old boys found that adverse environments shaped by low income, low maternal education, unstable family structure and harsh parenting were associated with a 19 percent shortening of white blood cell telomeres as compared to a cohort in more nurturing environments. These boys physically aged faster than their chronical age would suggest. Children with the most sensitivity (highest responsivity) to stress showed the longest telomeres in advantaged environments and the shortest in disadvantaged environments.75

Resilience

Resilience, the capacity to recover quickly from difficulties, is a characteristic of both individuals and communities. Parental bonding is a resilience factor, protecting children from the adverse effects of poverty on emotional and cognitive development.76

Community resilience is difficult to define and measure; the US Department of Health & Human Services defines it as "the ability of a community to use its assets to strengthen public health and healthcare systems and to improve the community’s physical, behavioral, and social health to withstand, adapt to, and recover from adversity".77 A resilient community is one that is socially connected, takes collective action, and has access to necessary resources.

Substantial risks to community health and well-being lie within community adversities such as climate change, urbanization and disparities. In the context of a natural or manmade disaster, increasing community resilience includes better preparedness and disaster planning, promoting community systems, and reducing threats to health. These are some steps communities and public health can take to build resilience:78

- Increase access to social services, public health and healthcare

- Promote physical and psychological health

- Build networks of social services, behavioral health services, community organizations, businesses, educational services and faith-based institutions

- Support those at risk by connecting them with services

- Build social connectedness

Interactions between Chronic Psychosocial Stress and Environmental Toxicants

Research shows impacts of combined stress and toxicants:79

- Animal models indicate that exposure to air pollution and stress in utero can harm cognitive abilities later in life more than either pollution or stress alone.

- Human evidence points to an association between maternal negative life events, exposure to allergens in mothers and children, and asthma.

- Financial stress after birth has been associated with more wheezing episodes in the first two years of life, a risk factor for asthma.

- Children who are exposed to stress in early development and exposed to air pollution may be at an increased risk for asthma compared to those who are exposed to just one or the other.

- Rodent models demonstrate that lead exposure before birth might affect the stress response system in a way that harms the body and may lead to greater impulsivity.

- Research in Southern California children found that living in a high-stress home is associated with more susceptibility to the negative effects of air pollution on the lungs.80

- In a study of children from birth to age seven, children who experienced high levels of air pollution in utero had lower IQ scores than those not exposed, but only when their mothers experienced material hardship.81

Selected Sources of Stress and Impacts on Health

Psychosocial risk factors for disease include family conflict, neighborhood violence, work stress and social discrimination; these factors can hinder mental and physical health.82

Domestic and Intimate Partner Violence

Global Domestic and Intimate Partner Violence

Globally, most data available is on intimate partner violence and sexual assault against women. An estimated 35 percent of women worldwide have experienced intimate partner violence over their lifetimes. Violence rates range from 71 percent of all women in Ethiopia to 15 percent of all women in Japan. Worldwide, up to 38 percent of all murders of women are committed by their partners.83

Domestic and Intimate Partner Violence: United States

Domestic violence includes violence from spouses, partners, parents, children, siblings or relatives. Three-quarters of incidents occur against women.84 In fact, it is estimated that a US woman is assaulted or beaten every nine seconds.85

|

Types of Domestic Violence.86

|

Most violence occurs around the home (77 percent),87 and 19 percent of all violent incidents include the use of a weapon.88

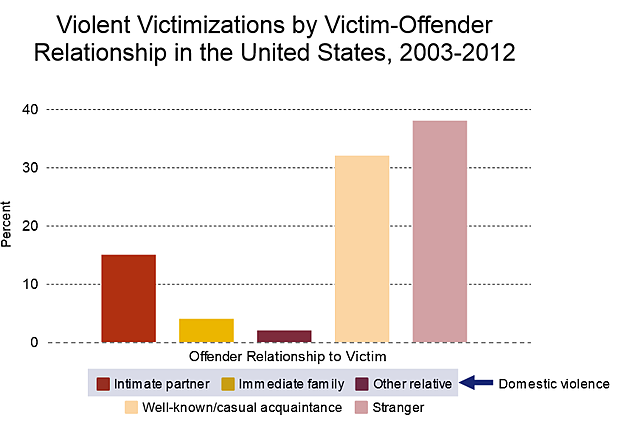

The National Crime Victimization Survey shows that between 2003 and 2012, domestic violence accounted for 21 percent of all violent victimizations in the US, with 70 percent of those from intimate partner violence (IPV).89

data from Truman and Morgan90

Preventing Violence in RelationshipsResearch in high-income areas indicates school-based programs can help prevent relationship violence among young people.91 |

Costs. Intimate partner violence accounted for $4 billion annually in 1995 in health care services and an additional $900 million in lost productivity.92 When these amounts are updated to 2003 figures, $8.3 billion in annual expenses are estimated, a combination of higher medical costs ($5.8 billion) and lost productivity ($2.5 billion).93

Health outcomes of intimate partner violence. In addition to death and injury (bruising, flesh wounds, fractures, brain injury and headaches), the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, immune, and endocrine systems are impacted from violence-induced stress, as discussed above.

|

Health Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence94 |

|

| Health conditions |

Infections Circulatory conditions Fibromyalgia Irritable bowel syndrome Chronic pain Central nervous system disorders Gastrointestinal disorders Joint disease Migraines Headaches |

| Reproductive conditions |

Gynecological disorders Pelvic inflammatory disease Sexual dysfunction Sexually transmitted infections, including HIV/AIDS Delayed prenatal care Low birth weight babies Perinatal deaths Unintended pregnancies |

| Psychological conditions |

Anxiety Depression PTSD Antisocial behavior Suicidal behavior in females Low self-esteem Inability to trust Fear of intimacy Emotional detachment Sleep disturbances Flashbacks |

| Social impacts |

Restricted access to services Strained relationships with health providers and employers Isolation from social networks Homelessness |

| Health behaviors |

High-risk sexual behaviors Harmful substance abuse Unhealthy diet-related behaviors Overuse of health services |

Child Abuse and Neglect

The CDC provides some 2014 facts on child maltreatment (either abuse or neglect) in the US:95

- 700,000 children experienced maltreatment, of which 27 percent were under the age of three

- Estimates exist that up to one in four children experience maltreatment in their lifetime

- 1580 children died from maltreatment

The CDC estimates total lifetime costs of child maltreatment at $124 billion annually.:96

Youth Violence

Any violence—including being a victim, offender or witness—in early childhood extending into young adulthood is considered youth violence. The US CDC provides some important US statistics to consider:97

- Youth violence is the third leading cause of death for those between the ages of 15 and 24.

- In 2012, an average of 13 people ages 10 to 24 were victims of homicide and 1642 more were treated in emergency departments each day.

- In 2013, 24 percent of high school-aged children were in a physical fight, 18 percent have taken a weapon to school, and up to 20 percent were bullied either at school or electronically.

- Youth homicides and violence-related injuries cost up to $16 billion annually in medical and lost time from work.

|

World Health Organization with CDC and other global partners created INSPIRE, a technical package of seven evidence-based strategies to end violence against children. |

Risk factors for youth violence:98

- A history of violence

- Substance abuse

- Delinquent behaviors

- Poor family functioning

- Poor grades in school

- Community poverty

Adverse Childhood Experiences

|

graphic from the CDC;99 click to zoom |

Adverse childhood experiences—ACEs—were first identified in the late 1990s. The risk for violence, victimization, and disease outcomes are heavily impacted by early childhood experiences. As shown at right, adverse childhood experiences can set children on an arduous path that increases risk for poor health behaviors, disease, disability, social problems and early death outcomes.100

- About two out of every three people have experienced an adverse childhood experience

- About one in five have experienced three or more ACEs

- There is a dose response: having more ACEs increases the risk for poor health and behavior outcomes

Examples of Adverse Childhood ExperiencesAbuse

Household challenges

Neglect

|

Outcomes associated with adverse childhood experiences:

- Alcoholism / alcohol abuse

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Depression

- Fetal death

- Illicit drug use

- Ischemic heart disease

- Liver disease

- Financial stress

- Risk for intimate partner violence

- Sexually transmitted diseases

- Suicide attempts

- Smoking

- Adolescent pregnancy

- Risk for sexual violence

- Poor academic achievement

Neighborhood Violence

Living in a neighborhood that experiences high levels of violence can have a devastating impact on people’s long-term mental and physical health. People who live in neighborhoods with high rates of violence suffer from trauma-related illnesses such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), at higher rates.101

|

|

Exposure to neighborhood violence is especially harmful for children—it has been shown to impair children’s cognitive abilities and academic performance, and potentially contribute to inattentive and compulsive behaviors.102

Other health outcomes are associated with negative characteristics of residential settings including fewer cancer screenings, cardiovascular disease, and the outcomes of violence discussed above. The risk or resilience of a community can directly affect the prevalence of child maltreatment.103

A 2015 review of national and international studies in urban areas found these associations. More research is needed in rural areas to understand if these factors are generalizable:104

- In the US community unemployment rate, per capita income, poverty rate and educational status were associated with intimate partner violence.

- Internationally, though lacking representation from Europe or the Middle East, intimate partner violence was associated with community norms, community attitudes towards women, women’s literacy, education, and murder rates. Women’s empowerment is also shown to be protective against IPV.

- Households with higher proportions of children were also associated with an increased risk of IPV.

- Community characteristics such as lower collective efficacy, social cohesion, higher perceived neighborhood disorder, and general social disorganization are associated with an increase of IPV. Although crime and violence rates themselves have mixed results with association to IPV, higher levels of perceived violence and worry about violence are associated with IPV.

Discrimination

Racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination exert a negative influence on mental health in a variety of ways. While experiencing discrimination within a person’s community is deeply stressful in and of itself, discrimination can also place certain groups at a higher risk of other adversities (poverty, segregation, unemployment, violence), which can also negatively impact health. Systemic racism, for example, raises exposure of communities of color to social exclusion and economic adversity, thereby placing them at a higher risk of stress, anxiety and chronic disease.105

Work Stress

Many factors in a person’s workplace can have a negative impact on their mental well-being. Factors such as poor work satisfaction, high demand, low job security, harassment and work disorganization can all cause people to feel substantially stressed while on the job. A 2016 investigation found 43 percent of working adults said their job negatively affects their stress levels. Others said their job negatively affects their eating habits (28 percent), sleeping habits (27 percent) and weight (22 percent).106

Behavioral Responses to Stress

People create many mechanisms for coping with stress, or sometimes these mechanisms arise as a product of stressful experiences without deliberate decisions. These mechanisms can be health-supportive, such as mindfulness, meditation, hobbies and the like. Other mechanisms can be health-destructive, such as smoking, alcohol abuse, substance abuse or even violence. Negative coping mechanism can deteriorate health in a way that causes further stress, thus becoming a destructive cycle. For many people with negative coping mechanisms, addressing the underlying stress may be necessary to overcome the negative health behaviors.

Stress and Addiction

|

|

Stress a powerful risk factor for both developing an addiction and relapsing back into addiction.107 Stress affects the reward pathways of the brain, those same pathways involved in stress, in ways that make people especially prone to become addicted to substances such as nicotine, alcohol and drugs.108

Health-supporting MechanismsCDC offers healthy ways to cope with stress:109

|

What we know about stress and addiction:110

- Those exposed to stress are more likely to use and abuse substances

- Experiencing chronic stress predicts continued drug use

- In research, stressed animals are more likely to self-administer drugs

- Stress increased cravings in abstaining cocaine users

- For smokers, those who received resources on managing stress were more likely to quit smoking

One reason stress is a such a risk factor for substance abuse is that substance abuse can temporarily reduce anxiety caused by stressful events. As stress levels become chronic, the body responds with dysregulated hormonal states and stress-related behaviors that can produce anxiety. This predisposes an individual to seek substances that temporarily alleviate this stress-induced physical state. After the 9/11 terrorist event in the US, researchers noted a corresponding increase in the sales of various street drugs.111

Those who drink alcohol report that doing so makes them feel relaxed and less stressed. However, using alcohol as a coping mechanism for stress, especially on a regular basis, increases alcohol's harm to the body.

Stress and Antisocial or Violent Behavior

Stressors early in life are heavily associated with aggressive tendencies later in adulthood.112 Universally, childhood maltreatment is a risk factor for conduct disorders, antisocial personality symptoms, and becoming a violent offender. Research has found that abused boys experiencing erratic, coercive and punitive parenting were most at risk of antisocial behaviors later in adulthood, with the earlier the experience the more likely the negative behaviors were. Early child abuse doubles the risk a person will engage in criminal activities later in life.113

Environments That Break the Cycle of Violence114

|

This "cycle of violence" describes the association between experiencing violence during childhood and the increased risk of either becoming violent or being a victim of violence. Although the majority of maltreated do not grow up to abuse others, we do know that one in six maltreated children becomes a violent offender and one in eight sexually abused boys becomes a sex offender.115 Victims of childhood abuse are at an increased risk of abusing their own children. Researchers also have found that up to one in seven children who experienced maltreatment in childhood also experienced abuse by their spouse. Violent experiences can be collective (gang membership), self-directed (harming oneself) or interpersonal (by a parent or other).116

This page's content was created by Lorelei Walker, PhD, and Nancy Hepp, and last revised in September 2016.

CHE invites our partners to submit corrections and clarifications to this page. Please include links to research to support your submissions through the comment form on our Contact page.