Around the world today, microplastics are largely unseen but ubiquitous. This makes it difficult to grasp the scope of the problem. Matt Simon’s book, A Poison Like No Other: How Microplastics Corrupted Our Planet and Our Bodies, sets out to show us exactly what we’re dealing with. In a recent webinar, Simon shared findings from his book with CHE Alaska.

A Poison Like No Other conveys the scope of the problem by continuously shifting focus, zooming in on the microscopic and zooming out to the global. The book begins on a remote mountaintop in Utah, where scientist Janice Brahney conducted a study using buckets set up to collect microplastics as they fell out of the atmosphere. Brahney’s study quantified the atmospheric fallout of microplastics at 11 remote and protected sites in the Western US. Extrapolating from the rates that plastics were collected, they determined that over 1000 metric tons of microplastics drape these protected lands every year.

As A Poison Like No Other explains, “[Brahney] calculated that each year the equivalent of 300 million plastic bottles fall on just 6 percent of the country’s landmass.”

When considering plastic waste in the ocean, we usually think of littered shorelines or the massive garbage patch accumulating in the Pacific. Again, microplastics are both easier to miss and much more widespread than most understand. A Poison Like No Other highlights scientists studying microplastics and their effects from the ocean’s surface to the seafloor, and throughout oceanic food webs. Because microplastics and plankton are moved by the same currents, they concentrate in the same biodiverse places. As plastics break down from micro to nano sizes, they gain the ability to migrate past the digestive system into the tissues of the creatures that eat them.

The story on land is similar. In one example in the book, wastewater treatment facilities that filter microplastics out of the water end up sequestering the microplastics into a byproduct called sludge. This sludge then gets applied to farmland as fertilizer. In addition to the plastic itself, microplastics are also contaminated with thousands of chemicals, many of which have been shown to have adverse health effects.

The Arctic

In the webinar, Simon highlighted how microplastics in the Arctic could exacerbate climate change. In a well-established feedback loop, warming in the Arctic causes sea ice to melt, which decreases albedo (the amount of light reflected off the ice) in Arctic waters. This reduced albedo causes those waters to absorb more energy and warm faster. As multicolored microplastics accumulate in sea ice, they could also decrease the albedo of the ice, causing it to melt more quickly.

“Scientists are finding more and more that these plastics are embedded in that sea ice and there is concern that these darker-colored microplastics are actually absorbing more sunlight into that ice and accelerating melting."

The higher the concentration, the greater the impact. Unfortunately, there’s already a significant reservoir of future microplastics out there. Even if we stop making plastic today, the plastic already in the environment will continue breaking down into microplastics for years to come.

A recent study looked specifically at plastic sediments in the Arctic Ocean and found that “the plastic pollution level in the Arctic environment will not reach its peak for many years, even after production and ocean input are drastically reduced or even completely ceased.”

What we can do

In his talk, Simon highlighted some solutions. A significant percentage of microplastics come from our synthetic clothes. Washing machine filters are available that can capture those microfibers from the wastewater. People can purchase those today and install them on their washing machines. France has passed a mandate that all new washing machines must include these filters, starting in 2025. The rest of the world, including the US, could enact similar mandates for these filters.

Simon also highlighted roadside rain gardens as a way to prevent plastic tire particles from washing into waterways. 6PPD-quinone, a chemical from tires, has been found to be highly toxic to some aquatic animals, such as coho salmon. Rain gardens can retain most of the microparticles that wash into them.

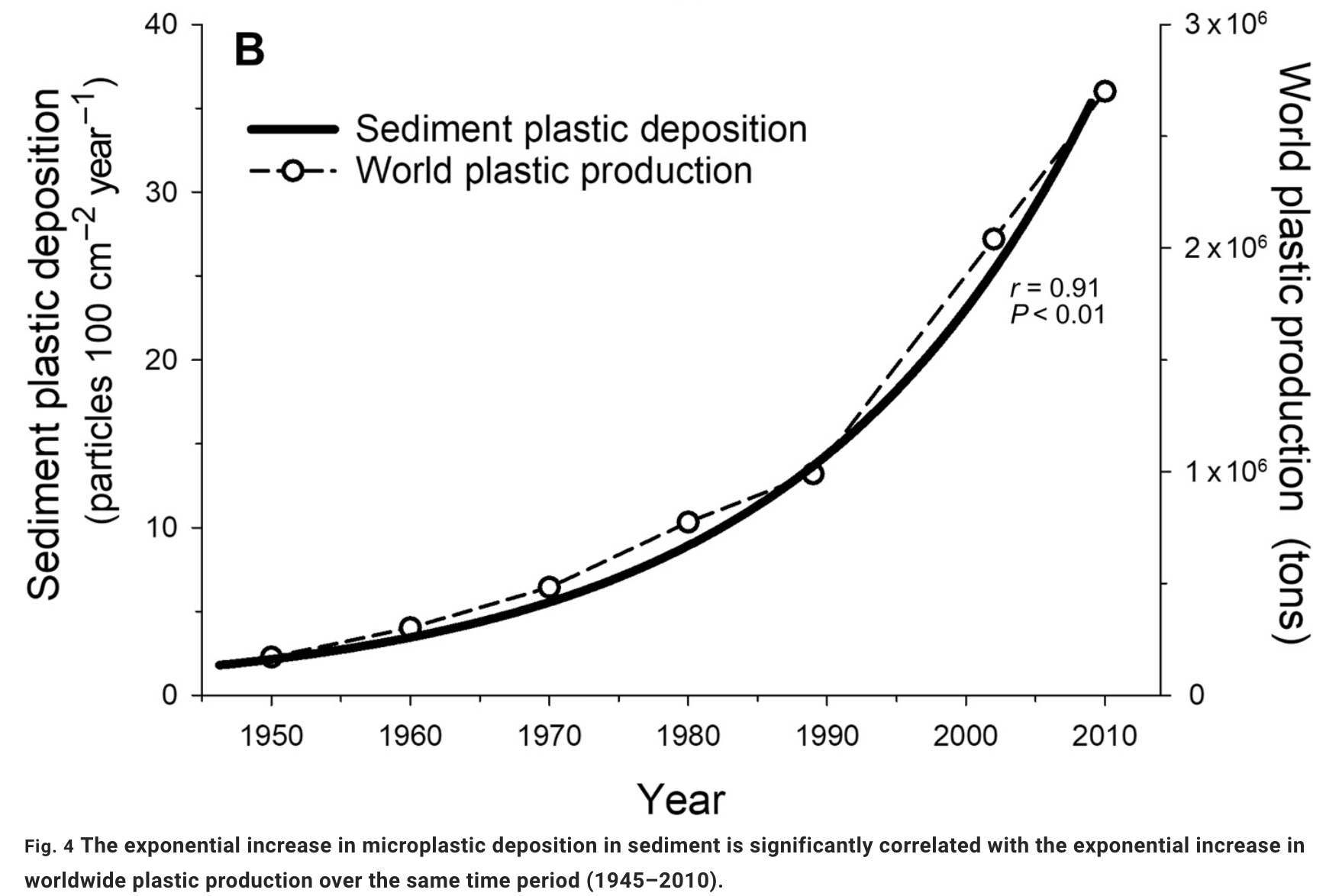

While there are individual actions we can take, Simon stressed that we need to tackle the problem at the source by reducing plastics production. Multiple studies have shown that the rate at which microplastics enter the environment is closely tied to global rates of production, which have increased more than tenfold since 1970. Plastic producers have made clear that they intend to continue this expansion.

“If you plot the sedimentary microplastic counts for each year on a graph, the curve overlaps perfectly with the exponential acceleration of global plastic production over the last eight decades.”

Jennifer A. Brandon et al., Multidecadal increase in plastic particles in coastal ocean sediments. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax0587 (2019). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aax0587

A global agreement?

UN negotiations are currently underway to establish an International Plastics Treaty to curb plastic production. The third meeting negotiating the outlines of the treaty will take place in Nairobi in mid-November, and approaches to addressing microplastics will be on the agenda.

Simon stressed that a primary goal of this treaty should be to set an international cap on production:

“These negotiations for the treaty need to have a mandatory cap, internationally, on production. We cannot allow countries to set their own goals like the Paris Agreement did for climate change.”

Negotiations of this international treaty are on a fast track, with the goal of completing a draft “legally binding agreement” by the end of 2024. For more information on the plastics treaty, be sure to check out our upcoming November 1 webinar, Plastics & Environmental Justice: What's Next for the Global Treaty?

Visit the webinar page to watch the full recording of CHE Alaska’s conversation with Simon, and to find out more.

This organizational blog was produced by CHE's Science Writer, Matt Lilley.