Microplastics are widespread contaminants found in our food, water, and air. They have been detected throughout the human body, including in our blood, lungs, saliva, liver, semen, placenta, and breastmilk.

Concerns are rising about how microplastics may be affecting human health. Although the research is still emerging, a growing body of evidence links microplastic exposure to adverse health effects.

A recently published review from UCSF’s Program on Reproductive Health and the Environment evaluated the existing research on the human and animal evidence assessing microplastic exposure to adverse human health outcomes.

In a recent CHE Alaska webinar, study authors Dr. Nicholas Chartres and Abena BakenRa discussed the results of their review.

Evaluating the evidence

To determine the quality and strength of the existing research, the study authors employed a rapid systematic review following well-defined methodology. Dr. Chartres explained their review process in detail.

At the outset, they decided to focus the review on health outcomes related to the digestive, reproductive, and respiratory systems. The reviewed studies all involved repeated exposure to microplastics. Exposure pathways studied were through food and water for the digestive and reproductive studies and through nasal passages or trachea for the respiratory studies. For the health outcomes, they looked for observable end points (such as birth defects) as well as biological responses that could be expected to lead to those endpoints (such as changes in hormones).

In the end, the reviewers identified 31 studies that fit their criteria:

"We included three human observational studies examining reproductive (n = 2) and respiratory (n= 1) outcomes and 28 animal studies examining reproductive (n= 11), respiratory (n= 7), and digestive (n= 10) outcomes."

After the relevant studies were selected, they were evaluated as a group for quality and strength. Quality was assessed based on the following eight factors:

- Risk of bias across studies

- Indirectness

- Inconsistency

- Imprecision

- Publication bias

- Magnitude of effect

- Dose-response relationship

- Accounting for confounding factors

Taking these into account, quality was assessed as high, moderate, low, or very low. From there, the strength of the evidence was assessed based on the following factors:

- Quality (as determined above)

- Direction of effect (for instance, evidence of an increasing adverse health effect with an increasing level of microplastic exposure)

- Confidence in effect estimates (considering factors such as the number and size of studies)

- Any other compelling attributes of the data that may influence certainty

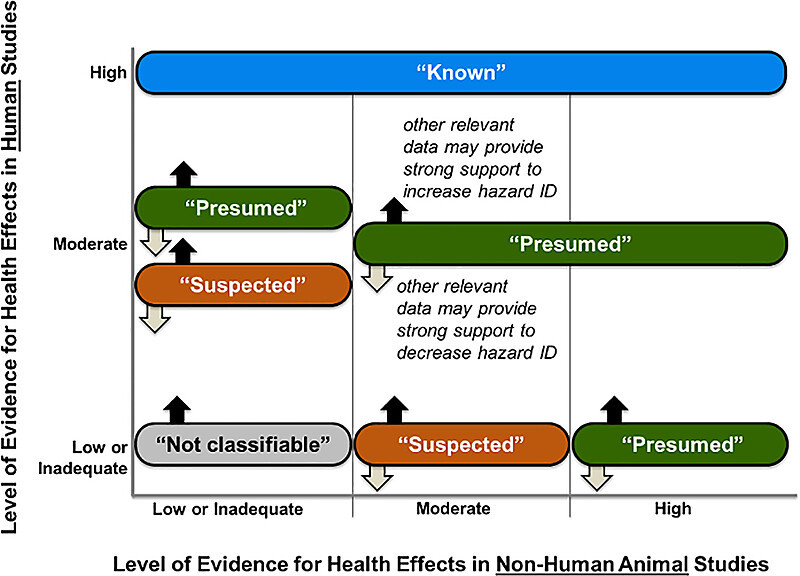

The strength analysis was used to make the final hazard conclusion statements. These statements were guided by the approach used by the National Toxicology Program Office of Health Assessment and Translation (NTP OHAT). The statements are broken up into four possible categories:

- Known to be a hazard to humans

- Presumed to be a hazard to humans

- Suspected to be a hazard to humans

- Not classifiable as a hazard to humans

The diagram below shows how these categories are defined. The x-axis shows the level of evidence for human studies. The y-axis shows the level of evidence for animal studies. As the diagram shows, for something to be classified as a “Known” hazard to humans, there would have to be high-strength evidence in human studies. If those human studies don't exist, then nothing can fall into the “Known” category. As this shows, when a hazard does not fall into the "Known" or "Presumed" categories, this often reflects a need for further research, rather than the safety of a chemical.

Conclusions

The study reached the following conclusions.

Digestive system

Microplastic exposure is “suspected” to adversely affect:

-

-

- Immunosuppression (high quality evidence)

- Gross or microanatomic colon/small intestine effects (moderate)

- Cell proliferation & cell death (moderate)

- Chronic inflammation (moderate)

-

Reproductive System

Microplastic exposure is “suspected” to adversely affect:

-

-

- Sperm quality (high quality evidence)

- Female follicles (moderate)

- Reproductive hormones (moderate)

-

Respiratory System

Microplastic exposure is “suspected” to adversely affect:

-

-

- Pulmonary function (moderate quality evidence)

- Lung injury (moderate)

- Chronic inflammation (moderate)

- Oxidative stress (moderate)

-

Taken together, this review indicates that microplastics pose digestive hazards potentially linked to colon cancer; reproductive hazards linked to poor sperm quality; and respiratory hazards potentially linked to chronic inflammation and lung cancer.

Chartres noted that the animal studies often only look at exposures to pure microplastic particles, rather than microplastics containing additional chemicals. The microplastics we are exposed to generally contain many chemical additives. In addition, the studies only evaluated one exposure pathway at a time, while people are exposed via multiple routes. These limitations likely lead to an underestimate of the actual human health harms of microplastics.

Call to action

Abena BakenRa highlighted the implications of their findings. Given the indication of harm, there's a clear need for additional research on the health effects of microplastics. She stressed that a lack of more definitive research shouldn’t preclude prompt action on a global and national level.

BakenRa argued that microplastics should undergo risk assessment and be regulated as a chemical class under the United States EPA’s Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA).

In addition, we can take the following actions:

- Prohibit the use of intentionally added microplastics in products

- Focus on capping/reducing plastic production in the International Plastic Treaty

- Phase out most toxic harmful plastic additives/most difficult to recycle polymers

- Phase out nonessential plastics

- Educate clinicians and the public about Plastics and microplastics as a driver of disease

For more on the review's methodology and findings, see the CHE Alaska webinar Microplastics & Health: A systematic review of recent science.

This organizational blog was produced by CHE's Science Writer, Matt Lilley.