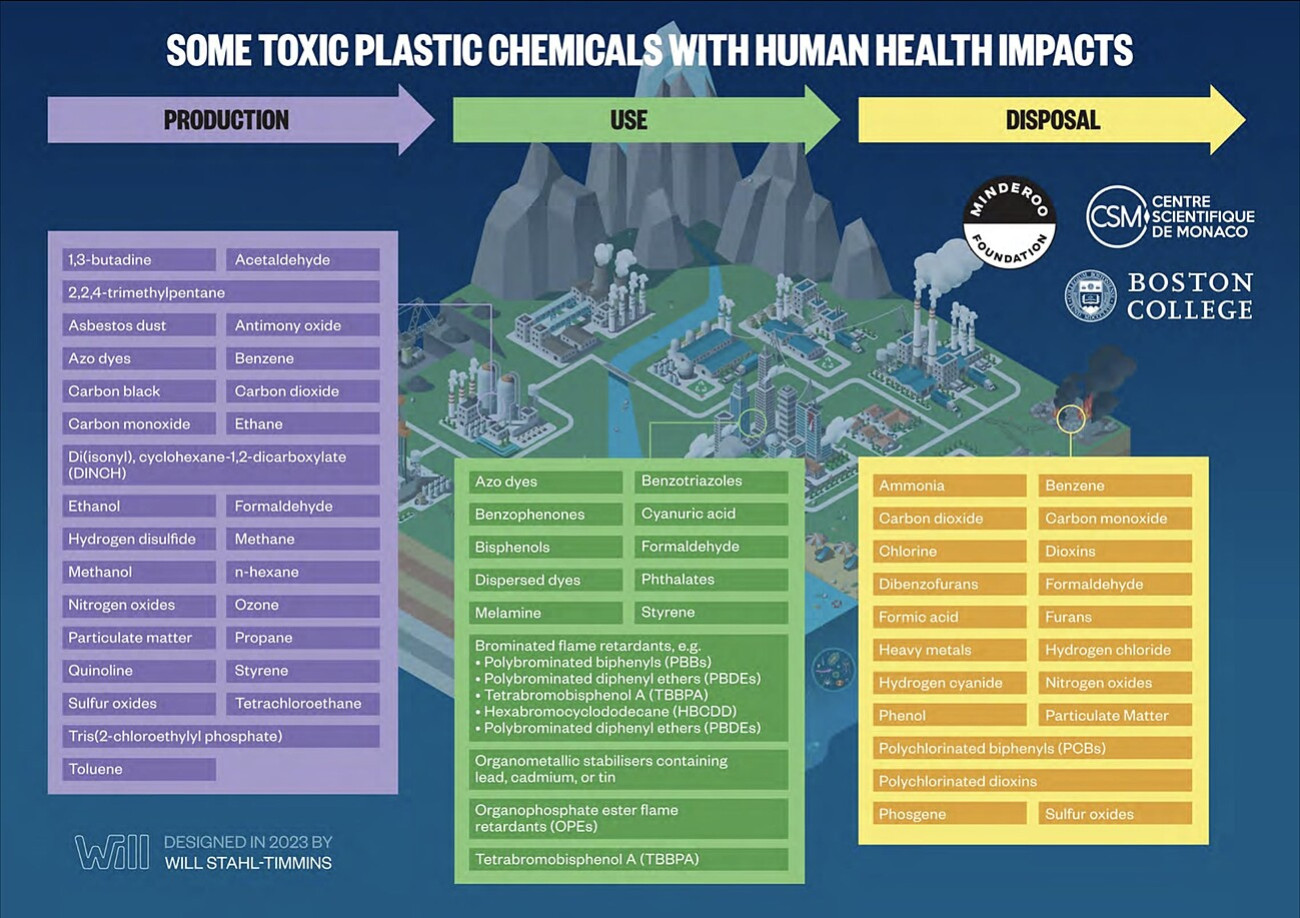

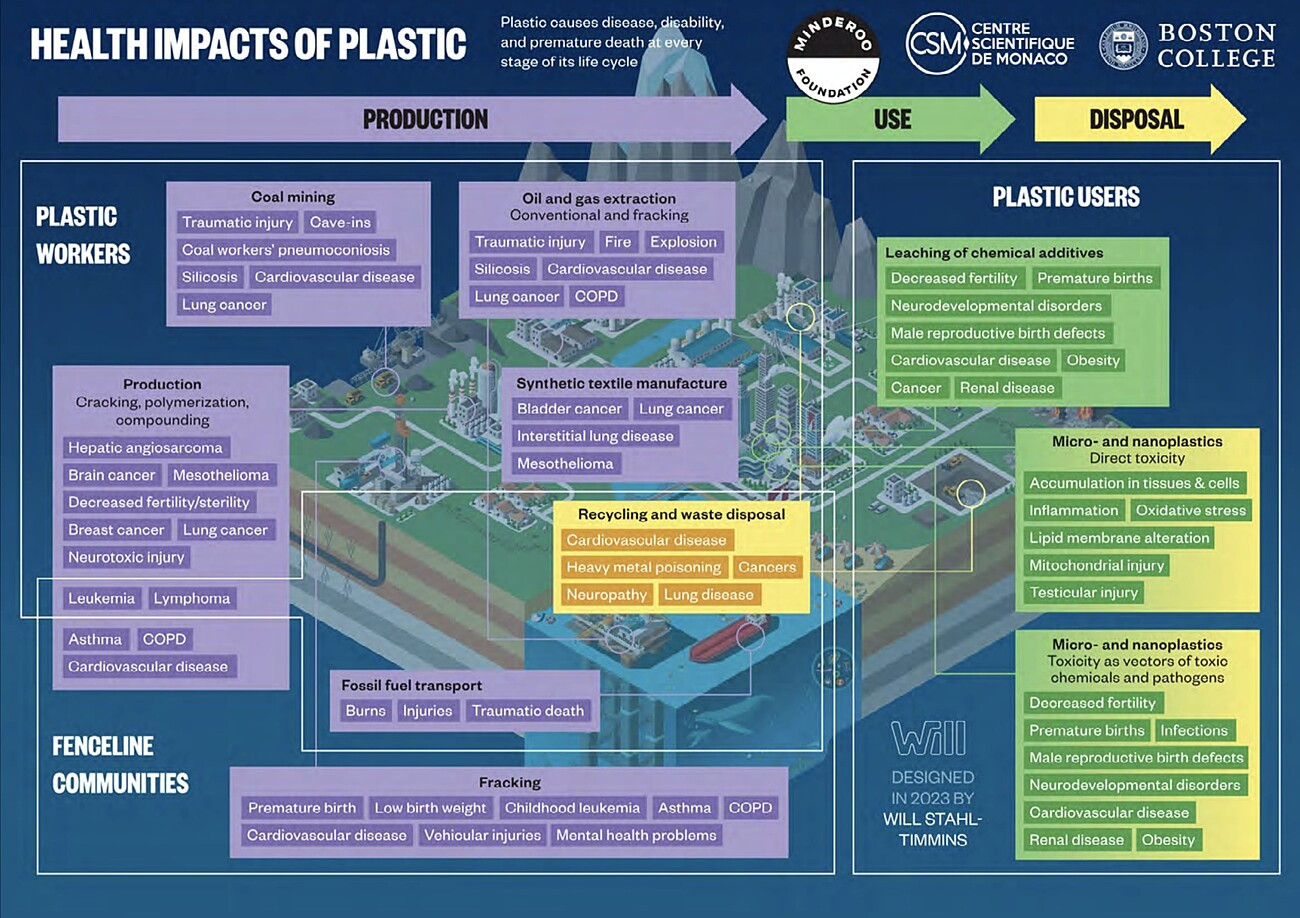

Chemicals used in plastics can be released throughout the plastic lifecycle. Harmful human exposures can occur at every stage, from feedstock extraction to production, use, recycling, and end-of-life disposal.

While it isn’t the focus here, it is very clear that plastics and plastic chemicals are also harmful to the environment. Estimates of the amount of plastic entering oceans annually vary from 500,000 metric tons 1 to ten times that amount. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature determined that plastic makes up 80 percent of all marine debris, from surface water to deep sediments.2

Given the volume of plastic materials being produced and used across the globe, the potential for harm to human health and the environment is enormous.

Overview of Chemicals

Petrochemicals are an intrinsic part of plastics. Ninety-nine percent of plastic polymers and the chemicals added to them in product formulation are derived from fossil fuels.

A 2024 report from the PlastChem Project3 used a hazards-based approach to identify known chemical hazards in plastics. The report identified over 16,000 chemicals that are potentially used or present in plastics. Of those, less than 6% are regulated globally, and many chemicals — particularly those used as additives — remain largely unregulated in the US and other countries.

The PlastChem report used the following criteria to identify hazardous chemicals:

A chemical exhibiting any of these properties is a chemical of concern. Using these criteria, the report found over 4,200 chemicals of concern in plastics. Of these:

- 3,844 have been found to be toxic

- Over 3,600 are unregulated on a global basis

- 340 exhibit at least 3 of the 4 possible hazard criteria

Micro- and nanoplastics (MNPs) are also of growing concern. These tiny particles are now found throughout the environment and have been measured in human organs.

Microplastics are one micrometer to five millimeters in length, and nanoplastics are less than one micrometer in length. MNPs can be composed of various combinations of thousands of chemicals used in polymer and product manufacturing, as well as additional chemicals that they absorb from the environment.

Common plastic chemicals

Plastic materials are various formulations of petro-chemical polymers. Some of the most widely used plastics include polyethylene terephthalate (PET), high-density polyethylene (HDPE), polystyrene, polyvinyl chloride (PVC), low-density polyethylene (LDPE), and polypropylene. These material formulations have different attributes, which determine how they are used.

Thousands of chemicals are added to these polymers in various combinations to enhance usability or function. A few additives that have garnered significant public and regulatory attention include:

Bisphenols: Bisphenols are used in plastic products like medical devices, toys, food containers, eating utensils, and cups. Epoxy resins made from bisphenols are routinely used as linings for food containers, including canned foods and beverages.

Flame retardants: Organophosphate flame retardants (OPFRs) are incorporated into plastics to prevent or delay combustion. They are also often used as plasticizers in consumer products and construction materials. OPFRs are a substitute for halogenated flame retardants, many of which are being phased out due to health concerns.

PFAS: Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a class of more than 12,000 chemicals used in industrial applications and consumer products, including plastic food packaging. Due to their persistence in the environment, these toxic chemicals have been dubbed "forever chemicals."

Phthalates: Phthalates are used widely in plastics, particularly PVC, to increase the flexibility and durability of the materials. They are also commonly used in food contact materials, personal care products, fragrances, and other applications.

Other commonly recognized plastic chemicals include heat and UV stabilizers, formaldehyde, melamine, alkylphenols, dyes, and more. The graphic below illustrates harmful chemicals used and released at different stages of the plastics lifecycle.4

Health Impacts

Given the ubiquity of plastic materials in products and the environment, health harms associated with exposure are a major concern. Many plastic chemicals are known to be endocrine disruptors, interfering with the normal functioning of the hormone system in ways that lead to disease, development delays, and other health harms.

We highlight here a small sample of health harms that studies have linked to widely used plastic chemicals.

Bisphenols are a risk factor for endocrine, immune, and oncological diseases. In some studies, diseases and disorders linked to exposure include prostate cancer, breast cancer, reduced sperm quality, early puberty in girls, and more. You’ll find a full list of suspected health impacts of Bisphenol A on our bisphenols resource page.

Flame retardants have been associated with various health issues, including reproductive harm, cancer, impaired neurological development, endocrine disruption, and immune disruption. Our resource page includes a table showing the associated health impacts of several classes of flame retardants along with some specific chemicals of concern.

PFAS are linked to adverse health outcomes including liver and kidney damage, reproductive and developmental harm, immune system impairment, and certain cancers. This 2024 CHE blog provides an overview of health impacts of PFAS exposure during pregnancy.

Phthalates are a family of chemicals with similar structures. Some are known to be endocrine disruptors and are linked to reproductive, neurological, and developmental harms.5 Phthalate exposure has also been linked to decreased fertility, particularly in men.6 Fetuses, infants, and young children are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of phthalate exposure.

Science Snippet: Dr. Philip Landrigan discusses the health impacts of plastics

Widespread MNPs raise concern

MNPs raise significant health concerns since they can enter the body through inhalation, ingestion, and potentially even skin absorption. MNPs can trigger inflammatory reactions, oxidative stress, and metabolic dysfunction in tissues where they reside. They have been found in placentas, infant feces, lungs, liver, breast milk, testes, heart, blood vessels, semen, urine, and blood. One study found MNPs in the human brain.7

MNPs have emerged as potential risk factors for a number of disorders, including cardiovascular disease and colon cancer, among others.8

Research of the human health effects of plastics is a rapidly evolving field. While the health effects of many individual plastic chemicals have not yet been studied, the evidence of health harm continues to grow. The Geneva Environment Network compiled many recent reports and studies on the health harms of plastic chemicals; this compilation of resources is available here.

Plastic chemicals & climate change

Plastic production is a significant contributor to climate change. According to a report released in 2021, the U.S. plastics industry’s contribution to climate change is on track to exceed that of coal-fired power in this country by 2030:9

"As of 2020, the U.S. plastics industry is responsible for at least 232 million tons of CO2e gas emissions per year. This amount is equivalent to the average emissions from 116 average-sized (500-megawatt) coal-fired power plants."

Plastics may also be accelerating climate change indirectly. In a recent webinar, author Matt Simon highlighted how microplastics are contributing to a feedback loop of warming in the Arctic. As sea ice melts, the amount of light reflected off the ice in Arctic waters decreases. This in turn causes those waters to absorb more energy and warm faster. As multicolored microplastics accumulate in sea ice, they could also decrease the reflective power of the ice, causing it to melt more quickly.

"Scientists are finding more and more that these plastics are embedded in that sea ice and there is concern that these darker-colored microplastics are actually absorbing more sunlight into that ice and accelerating melting."

A wide range of human health harms have been linked to climate change.

Exposure Sources

Plastic products are ubiquitous, and while awareness of the plastic problem is growing, global production continues to increase. Each stage of the plastic life cycle, from extraction through formulation, production, use and disposal, can cause human exposure to plastic chemicals. The 2023 report Hidden Hazards: The Chemical Footprint of a Plastic Bottle documents the hazard plastic can pose at each stage of the process.10

In many cases, chemicals used as additives are loosely bound to plastic polymers and can easily leach into the environment (or onto food, in the case of food packaging). The graphic below illustrates potential exposures to plastic chemicals and related health harms at different stages.11

Micro- & nanoplastics

Micro- and nanoplastics (MNPs) are continuously shed from consumer products during use, recycling, and after disposal. In addition, MNPs are intentionally added to some personal care products. MNPs are now widespread throughout the global environment, with human exposure occurring via contaminated air, water, soil, and food chains.12

Reducing Exposures

Given what’s understood about the health harms of plastic chemicals, plus the many unstudied potential hazards, the best approach to protecting public health is dramatic reduction of plastic production and use. While some measures can be taken at a personal level, crafting effective policies at all levels to reduce reliance on plastics is essential.

Regulation

In 2022, the United Nations Environment Assembly resolved to develop a global agreement on plastic pollution. Treaty negotiations are ongoing, and the health harms of plastic chemicals has emerged as a key issue.

Recommendations from environmental public health organizations (see, for example, Protecting the Developing Brains of Children from the Harmful Effects of Plastics and Toxic Chemicals in Plastics) involve sweeping changes to protect public health, including:

- substantial reductions in plastics production;

- re-design with phaseout of the most toxic plastic polymers and hazardous additives;

- full transparency and public disclosure of the identity of chemicals used in making plastics, including additives;

- assurances that disposal and recycling does not result in the release of hazardous chemicals or materials into the environment or into recycled products; and

- prevention of incineration of plastic waste as a means of disposal.

The PlastChem project report mentioned above lays out a roadmap for safer, sustainable policies on plastics at all levels of government.

Unfortunately, national safety measures for plastic chemicals are not common in the United States. A recent paper by the Consortium for Children’s Environmental Health called for a “fundamental revamping of current law” to better protect children from plastics and other harmful chemicals of concern.13

Many state-level policies have been adopted or are moving forward that address plastic chemicals. Nineteen state laws in 13 states have been adopted as of early 2025, with 16 additional policies moving forward.14

The focus of these policies range from restricting use of the most toxic plastics (including PVC, polystyrene, and polycarbonate) to phasing out the worst chemicals found in plastic packaging (such as phthalates, bisphenols, and PFAS). Some state policies mandate source reduction and chemical transparency, and others push back against so-called “chemical recycling.”15

Personal prevention

While systemic changes are urgently needed, reducing personal use of plastics can both help reduce an individual's exposures to harmful plastic chemicals and drive demand for safer products. Examples of individual and household steps include:

- Carry reusable water bottles and coffee mugs

- Decline plastic straws and utensils

- Avoid plastic food packaging (and never microwave in plastic), including plastic teabags

- Replace black plastic cooking utensils

- Avoid single use plastics whenever possible

Action at the community level can also help reduce exposures to plastic chemicals. Some impactful measures include:

- Bans on plastic grocery bags

- Replacement of artificial turf fields and playgrounds with sustainably managed grass

- School district policies supporting plastic-free cafeterias

To explore recent webinars, blogs and partner resources on plastic chemicals, see our Key Topics page.

This page was created in January 2025 by CHE Director Kristin Schafer, with input from Ted Schettler, MD, MPH, and editing support from CHE Science Writer Matt Lilley.

CHE invites our partners to submit corrections and clarifications to this page. Please include links to research to support your submissions through the comment form on our Contact page.